In the fields of life sciences and medical research, animal experiments are an essential part of many studies. People often use the term “lab mice” to refer to experimental animals, but mice are far from the only animals used in scientific research.Experimental animals also include nematodes, zebrafish, fruit flies, naked mole rats, rabbits, dogs, monkeys… and yes — our beloved cats.That’s right: this adorable species, adored by countless followers of the “Cat Church,” actually has another identity as well — certified, working experimental animals.Now, let’s take a look at some of the stories about cats hidden behind several Nobel Prizes.

-

1912: Cats Undergoing Kidney Transplants

The connection between cats and the Nobel Prize dates back to 1912. That year, French surgeon Alexis Carrel was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work on triangulated vascular suturing and organ transplantation. Although Carrel later faced criticism for his political beliefs, his early achievements earned him the title “Father of Organ Transplantation.” Alongside this title, he is remembered for a series of organ transplant experiments on various animals.The most widely circulated story about Carrel may be his successful transplantation of two kidneys from one dog to another dog that had already undergone kidney transplantation. In fact, he also successfully performed double kidney transplants on cats, and in 1908, he completed the first successful single-kidney transplant in a cat, demonstrating that a single kidney is sufficient to maintain normal life functions.Thanks to Carrel’s work proving that “removing both kidneys and relying on a single transplanted kidney can save a life,” people realized that a donor only needs to donate one kidney to save another’s life. This laid the foundation for later living-donor kidney transplants.Decades later, in 1954, John P. Merrill and David Hume at Harvard University successfully performed the first living-donor kidney transplant in humans, transplanting a kidney from an identical twin to his brother suffering from uremia. The recipient lived an additional eight years, while the donor lived to 79 in good health. At the time, uremia was considered a terminal illness with a poor five-year survival rate, and the success of living-donor kidney transplantation offered new hope for patients’ survival.

-

1932: The Cat Classroom

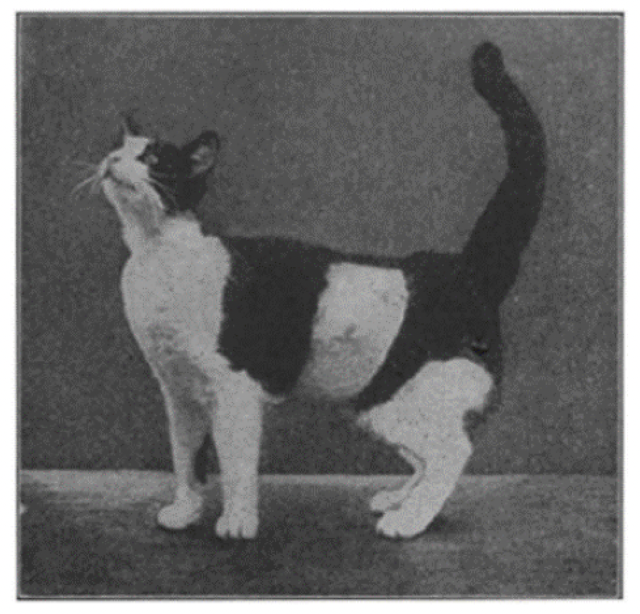

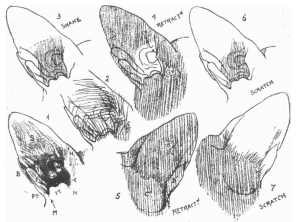

Around the same period that Carrel’s cats were undergoing organ transplants, neurophysiologist Charles Sherrington was using cats to study neural reflexes and proprioception, work that earned him the 1932 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.While teaching at Oxford University, Sherrington was always accompanied by cats. He taught a course on mammals, often with five or six cats present in the classroom as teaching aids. His laboratory, filled with experimental cats, became known among students as “The Cat Classroom.”In 1898, Sherrington discovered that if the brainstem between the midbrain and the lower hypothalamus was transected in cats, they exhibited a stiff posture — heads and tails raised, spines rigid, and limbs extended. This phenomenon, called decerebrate rigidity, is caused by over-contraction of the extensor muscles (also known as anti-gravity muscles), which straighten the limbs or other parts of the body.From this, Sherrington discovered the stretch reflex, a reflex that occurs when muscles are excessively tense. He was also interested in how cats stand and walk. In 1910, he described that even after removing the brain, cats could stand and perform rhythmic alternating steps, suggesting that standing and walking reflexes originate from sensory input in the lower limbs, not the brain, transmitted directly through the spinal cord. This advanced the understanding of motor control.By 1917, Sherrington focused on the reflexes of cat ears, meticulously defining and studying retraction, folding, covering, itching, and shaking reflexes, proving these reflexes do not require brain involvement. In his papers, he noted:“The cat’s pinnae are sensitive and flexible, capable of numerous reflexes. One, which I mentioned in earlier research, was previously unnoticed by others, though undoubtedly encountered by other observers.”He also found that cats could reflexively move their tails or raise fur in response to dog barks, cat meows, and bird calls, without using the brain. These studies of cat ear and tail reflexes revealed that neural reflex types are far more complex than previously imagined.

-

1981: The True “Eyepatch Cat”

If a mascot had been chosen for the 1981 Nobel Prize ceremony, it could very well have been a cat. That year, the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to two research teams, and both had used cats extensively in experiments.The first team, led by Roger Sperry, studied functional specialization of the cerebral hemispheres. The second team, David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel, explored information processing in the visual system.In Sperry’s time, anatomists had discovered that the two hemispheres of the brain were connected by a bundle of fibers called the corpus callosum, about 10 cm long. Its structural connection was known, but its functional role was unclear. Sperry decided to sever the corpus callosum to see whether the two hemispheres could still communicate information.He focused on visual signals, using one-eye occlusion to isolate inputs to each hemisphere. In his 1953 study, he placed light-blocking eye patches on cats and taught them to distinguish squares from circles. Cats learned the shape with the right eye first, then switched to the left eye. In cats with intact corpus callosums, the second learning session reinforced the first, increasing the learning rate. But in cats with severed corpus callosums, knowledge learned by one eye did not transfer to the other eye, showing that the two hemispheres could not communicate.This discovery confirmed the corpus callosum as the bridge for inter-hemispheric information transfer. Sperry also realized that patients undergoing corpus callosum surgery for epilepsy were ideal human subjects for studying left-right brain functions. This established him as a leading figure in cognitive neuroscience.Meanwhile, Hubel and Wiesel focused on cats’ eyes, since cats’ short snouts and facial structures made them suitable models for visual experiments. Their 25-year collaboration explored visual neural mechanisms, recording the activity of individual neurons in the visual cortex while showing cats light patterns of different orientations and wavelengths.They found that some cortical cells were highly sensitive to light orientation, while others were sensitive to wavelength. They also studied monocular deprivation in kittens, sewing one eye shut during the critical developmental period. This showed that visual coding forms postnatally and requires visual stimulation, leading to the concept of a “critical period” for visual development.

Building on this foundation, later research demonstrated that it is not only vision that requires early developmental stimulation from the external environment. Hearing, language acquisition, motor skills, and many other neurological functions also depend on appropriate sensory input during early development.The introduction of the concept of critical periods in neural development opened new doors for understanding and treating childhood conditions such as congenital cataracts and strabismus. When surgery and visual correction can be performed within the critical window of visual development, many children can avoid lifelong visual impairment or even blindness.In fact, there are many more stories about cats in scientific research. Numerous studies closely related to human health — including research on pancreatic and hepatic physiology, the discovery of acetylcholine, the development of antidepressants, and much more — all have cats playing an indispensable role.So today, let us say it together:Thank you, cats.